Dyvik Kahlen is an architectural practice. Recently realised works include the urban plan for a shared park, a four-storey apartment building, a glass house and a restaurant.

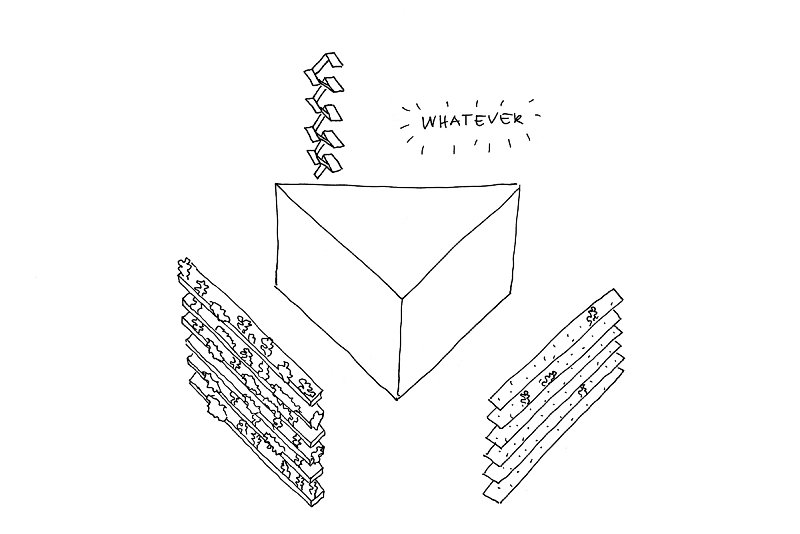

The ongoing project Daily Camping explores functional objects that inspire flexible and unconventional ways to inhabit buildings.

Porto

Dyvik Kahlen, Office & Workshop

Praceta Eng. António de Almeida 70 R/C 3

4100-065 Porto, Portugal

+351 910 156 057

Palma

Dyvik Kahlen, Office & Showroom

Carrer Sant Elies 4, Local Izquierda

07003 Palma, Spain

+34 646 864 181

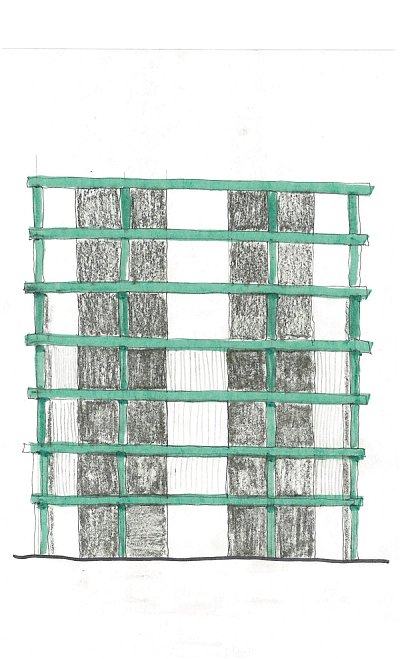

This book brings together a collection of buildings from the twelve students of ADS5’s Masters in Architecture at the Royal College of Art, class of 2020. These twelve buildings are the result of an ongoing exploration at ADS5 around ambiguous architecture, or the design of buildings that fulfil functions beyond a pre-determined program. These buildings are simple and generic, and have an inherent flexibility and generosity at heart that we believe is fundamental to their longevity. Inhabitants are treated as ‘guests’ who, rather than follow a prescriptive way of being in the space, appropriate it in ways we cannot yet predict.

Our lives move fast. External factors are quickly changing the way we live, move and interact with each other. Traditionally, we could attribute this to advances in technology, environmental concerns, evolving social structures and behaviours, economic or political shifts. Most recently, and somewhere around the start of the second term of this academic year, we’ve all had the opportunity to experience these shifts at a grand scale as a result of the ongoing pandemic, accelerating change in ways we could not have foreseen.

While the fast evolution from physical to digital permeates every aspect of our lives, architecture remains a relatively slow discipline. The time required to take a building from concept to construction means we are always catching up with the world beyond our discipline. Developing an architectural concept is an exercise in reduction and refinement, like a slow simmering stock, where all redundant elements evaporate over time in order to reveal the essence of the flavour.

In order for architecture to preserve its integrity and remain resilient in this context of anachronism, we believe the purpose of a building needs to be defined less by a pre-determined function and more by its potential to be appropriated for different uses and desires over time. Its value defined through character, generosity, atmosphere, proportions, beauty and the degree to which its spaces can be loved, re-used or mis-used over time.

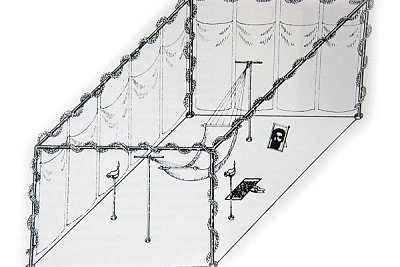

We approach the building as a landscape where potential uses are simply defined through the presence of elemental infrastructure: circulation, ventilation, water, electricity and thermal comfort. This landscape is appropriated in various ways through the course of its life by temporary ‘guests’, such as furniture, nature, events and people. We surround ourselves with objects, some have meaning or represent a memory, while others are simply there to fulfil a function, like making coffee or reading a book. How we choose to position these objects in a room has the potential to alter our perception of that room, its focus and atmosphere. They portray a person, a way of living.